My wife and I were on our way to the beach and had just gone through town when my wife said, “Remind me to stop at the drugstore on our way back.”

Later on, I reminded her, “Don’t forget to stop at the drugstore.” We stopped and the task was accomplished.

“So how much credit do I get for this?” I asked. I know that you wouldn’t ask that, but I did. My wife knows me and my quirks. I just wanted a kiss, but the exercise of assigning credit is something I also enjoy. You and your spouse wouldn’t do this because you’re normal. And if you did, you’d probably just say it’s 50-50. That’s easy enough.

What if she remembered in the end, though, not you? Is that still 50-50? My wife would definitely not think so.

And what if you forgot and your wife forgot? Who gets the blame? Is that 50-50? Blame leads to fights, especially if each person is trying to put it all on the other.

It’s probably a dumb argument. You’re a couple. This was silly.

But, in my world, which is sports, assigning blame is not an argument but a calculation. In basketball, if you made the perfect pass to a wide open shooter and they missed the shot, do you solely blame the shooter? No.

What if the shot was at the end of the shot clock when there was no choice but to take the shot? Also no.

What if the pass was a little bit off to the side? Well, then there is clearly some blame on the passer.

What if the pass was easy to make and the shot was hard?

You’ve probably never thought so much - just four small paragraphs - about dividing blame and credit. Your head wants to go rest with a TikTok video now.

But this is the kind of thing I had to think about to develop a metric to evaluate basketball players. How do I divide credit and blame in very specific events?

My answer initially came from the intuitive. I watched games and subjectively assigned credit and blame, usually without writing anything down. It was in my head. A big long thought process that took the place of watching commercials or listening to broadcasters.

A player would make a pass that led to a made shot and I’d think about how much credit they should get. The scorekeepers would award an “assist” to the passer - giving some kind of division of credit implicitly, even if through a different label.

If it was a pass threaded through defenders for a layup at the rim, I’d instinctively give more credit to the passer. If it was a simple pass to a shooter at the arc, I’d give a little less to the passer. If it was a so-so pass to a player who caught it and had to heave it at the buzzer, he may still have gotten an assist, but I’d lower the credit on that.

Instinct and feel led me to thinking about a lot of different situations, not just passes leading to shots. How to give credit to a defender that shuts down a scorer one-on-one? Or what if he gets some help from teammates? After that missed shot, how to give credit to the player who gets the defensive rebound? How much to blame the defender who helps on someone else’s man then has to get out to his man after the pass is made?

What about the credit and blame on a made shot from half court at the end of a quarter? Do you give 100% to the shooter? That feels right. But what about the defense? It was a lucky shot. You can’t just ignore it; you still have to assign blame. Maybe it was just 20% to each of the defenders.

I wrestled with a lot of basketball situations.

There are all sorts of life situations where blame and credit can be divided, well beyond when a spouse asks you to remind them about something.

If you left your credit card at the restaurant, maybe you blame yourself. Maybe you blame your date for distracting you (probably not a good idea). Maybe you blame the waiter because he left the card in a strange place. Maybe you blame the musicians who were so good that they distracted you.

If your wallet got stolen, you blame the person who stole it.

If you were in a car accident, the cops and the insurance agencies try to sort out whose fault it was - you or the person in front of you who didn’t hit the brakes early enough or the person in front of them who stopped suddenly for a dog in the road.

Maybe you blame the weather when your knee injury starts flaring up.

Maybe you give credit to the driver who actually stopped at the crosswalk to let you cross the street.

It happens every ordinary day. Something goes wrong and you want to blame someone. Something goes right and, if you’re a halfway decent person, you don’t take full credit.

These little discrete events happen. Some of them aren’t so small in their impact. Some are actually quite big, like a car accident. Some are smaller, like having to go back to a restaurant for the credit card that the staff set aside (giving them credit for that).

Credit and blame are real life things.

But no one much cares about how to actually divide them, at least not until they become bigger and broader, which is long after a lot of little things have fed into them.

Blame for the unemployment rate going up. Blame for a divorce. Credit for the unemployment rate going down. Credit for the third-quarter earnings of a corporation. Blame for how tax dollars get wasted. Blame for a plane crash. These are big things that are the results of a lot of actions.

People want to divide those big and broad things. That’s harder. There isn’t one specific event that you can divide. There are lots of them that add up to something better or worse than where things began.

I thought about all of this a lot over the last thirty years. I thought about it because it’s so common in daily life. I thought about it because basketball needed it, with coaches dividing credit and blame in every film session.

And I thought about it because my brain works well with numbers. My brain likes things to add up. And my brain doesn’t want things to be purely subjective. There had to be a way to make it concrete, not just based upon some intuitive feel.

After about fifteen years of thinking, I actually figured out how to do it.

The critical element was something that coaches say, “We win and lose as a team. We just need to do our own jobs.” They said it enough and I guess it finally triggered my math brain. I needed to align the incentive of every player to that of the team, considering the job they were doing. If the team did well, each player would do well. If the team did poorly, each player would also. But how much they would get incentivized was about them making sure that they weren’t taking on the hard job without also getting the bigger reward. They also wouldn’t settle for the easy job without knowing that their chance of getting big blame was pretty small.

There are equations for these things. They form the basis of a metric to measure basketball player performance. Teammates get differing credit based upon their role in each event in a game. They get differing levels of blame when things go wrong. Because the credit and blame is at the level of an event, it makes the performance easy to slice into different time frames or different situations, including ones that may illustrate the causes of a player doing better or worse.

The assignment of credit and blame in my world has not been about blaming or shaming the players. It’s about identifying ways to make players better and rewarding them appropriately. That’s also a fine line that coaches walk when working with players. They have to identify when a player does something wrong so that it can be corrected, not to blow up their character.

Notable coaches like Gregg Popovich and Erik Spoelstra are noted for their ability to communicate, including communicating the bad stuff without turning the players into villains or incompetents. They emphasize the reason, the cause, the way to fix it, not the character of the person they’re trying to work with.

And that’s not the way most people use blame. Blaming on a broader scale is usually an attack on character, a difficult-to-change aspect of who a person is. The longer-term aggregation of doing enough small events wrong can make a person seem like a bad person or a bad player. It can seem like who they are, not a sequence of events where they could have done better to help the team.

And helping the team is the focus. With that focus, you don’t harp on people’s character. One example of that comes from a story in my book, Basketball Beyond Paper. In that story, Miami was struggling in the 2016-17 season before it completely turned its season around. Their coach, the aforementioned Spoelstra, would call a star player into his office in advance of a film session where he would highlight a play that the star didn’t do well on. It would be to prepare and inform the star so that teammates saw that there weren’t favorites being played and that the actual things that the star did could get fixed. It was about getting the team better, spreading blame appropriately when things went wrong so that those parts could be fixed, so that anxiety about disproportionate blame wasn’t a problem.

Communicating credit and blame so that players stay aligned with the team is a lot easier if the credit and blame are actually aligned themselves.

One of the visual examples I have used to describe credit and blame is a simple game of catch. You and a friend are just throwing a ball back and forth. You throw it and your friend catches it, then throws it back, where you catch it and repeat. Every time a catch is made, the team accomplishes what it wanted and credit can be divided. Every time a catch isn’t made, the team fails and blame can be divided. Was the throw off-target or did your friend just lose concentration? Or have bad motor skills? Or not see the ball in the sun?

If you actually go outside and play this game (someone will yell at you if you do it indoors, I’ve found), you’ll start getting a feel for it. You’re doing some math by feel. When the ball is short and there is no catch, you’ll blame the thrower. If the ball was short, but not as short, maybe the catcher could have made more of an effort to catch it, so you blame the thrower a little less. If the ball was short and the catcher made a scoop catch, you give them more than the 50-50 credit you were probably giving on the routine throws.

If you decide to actually spread out, get farther away from each other, the instinct is that now the thrower’s job gets harder, especially if you say that the catcher has to stay in some box, however you define it. So, again, that 50-50 credit you may have given initially starts changing, in this case toward the thrower whose job to be accurate is more difficult if the players are farther apart.

As I said, you’re doing math and you don’t know it.

The math feels simple, right? For short throws, the throws are accurate and the catch is easy, so about 50-50 for credit, a little more to the catcher if the throw goes a little astray. As the players get farther away, more credit to the thrower. More blame on a drop of a well-thrown ball than on a drop of a poorly thrown one. What are the numbers? You don’t know exactly, but …

There is a formula for that and it’s actually remarkably easy. Let me say what the formula does in words, if that helps you. The credit for the catcher is the difference between the thrower’s chance of being accurate and the catcher’s chance of catching it, plus the value of 1, all divided by 2. I don’t know why those words aren’t scarier than the formula,

but some people like it that way. Knowing what the chances are, pthrower and pcatcher, is a little tricky, but someone could collect data on that.

If the thrower’s job gets harder, pthrower goes down, and the credit given to the catcher goes down, too. If the catcher’s job gets harder - maybe because it is thrown less accurately - then pcatcher goes down, and the credit to the catcher goes up.

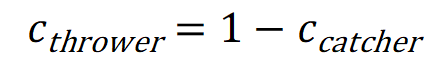

You probably know this, but the credit to the thrower is just what’s left, 100% minus the credit to the catcher or

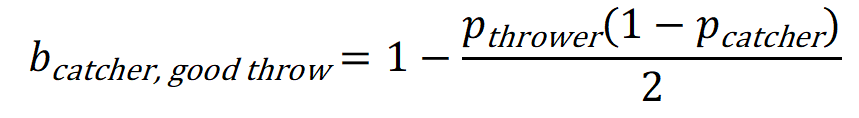

Defining the blame if no catch is made is actually a little more difficult in concept, but not in the math. What makes the concept difficult is this: the thrower could make a terrible throw, the catcher could drop a good throw, or there is some spectrum in between where the throw is mildly off-target and the catch is harder. In the first case, the thrower failed. In the second case, the catcher failed. In the third case, both failed to some degree.

Ignoring how to actually assign the probabilities here, the formulas for these situations are, respectively,

See? The formulas are simple. As mentioned above, defining exactly what the values of pcatcher and pthrower are - that is a little tricky. You can imagine that they change depending on how far apart the players are, for one thing. You can also imagine splitting the catchable range up into an “easily catchable” range above the belt, as well as a “more difficult” range outside of that to some distance that is not catchable. You can probably imagine several different ranges where the probabilities change a bit. That is all possible.

But let’s stick with a few cases:

A very good throw in the easily catchable area when the players are close together. Assign values of pcatcher = 95%, pthrower = 90%

A very good throw in the easily catchable area when the players are far apart. Assign values of pcatcher = 95%, pthrower = 80%

A throw to the more difficult range when the players are close together. Assign values of pcatcher = 70%, pthrower = 90%

A throw to the more difficult range when the players are far apart. Assign values of pcatcher = 70%, pthrower = 80%

The credit and blame assigned in these four cases works out like this.

The catcher gets anywhere from 43% to 60% of the credit across these situations, more when the thrower doesn’t particularly make the catch easy, especially when the throw should have been easy. You felt it should be around 50-50 and it is.

If the catcher fails, he gets 87-98% of the blame. So the thrower can make a perfect throw and still share some small percentage of the blame. That’s the nature of being on a team (and being an imperfect person).

It’s the same thing if the thrower fails - the catcher still gets some of the blame. If you think back to making the throw longer, you automatically make it harder for the thrower to do his job. Just by having his role, he is taking on risk of failure, which is why there still has to be some blame on the teammate.

For the blame when both fail, it makes sense to talk about where these formulas come from.

The idea behind a team is that players do a job, those jobs may be different, but ideally they’re willing to take on any job. They should feel incentivized to do so.

That’s what set up the equations above. Average players should feel like they will get equally rewarded or penalized regardless of the job they’re doing. By doing the hard job, they’re not putting themselves at risk of looking like the scapegoat. By doing the easy job, they’re not looking like they’re shirking responsibility.

Basically, an average player is incentivized to do their best at whatever job they have to do. If each player does their job, the team succeeds and the rewards are set up right. If even one player fails at their job, the team fails and the blame for failing is still set up right. The math is set up for that, with the solutions shown above.

But that isn’t the only kind of team. Another kind of team is one where it’s sequential: one player must do a job, then another does theirs if the first was accomplished. If the first player failed at their job, then the second player doesn’t have anything to do. The formulas that align credits and blames correctly are a little different,

This is actually probably a better fit for the playing-catch game. A thrower who makes such a bad throw that the catcher has nothing they can do - that is a little different than both failing. What exactly is “both failing” in the playing-catch game? If you use the sequential results with the same inputs, you get these divisions of credit and blame:

These are almost the exact same numbers as above, except that the last column doesn’t exist because the catcher can’t fail if the thrower fails. The change in the results is that the catcher gets a little less credit when they succeed and a little more blame when the thrower fails, but those differences are small. Those little shifts are just because the catcher has less responsibility with this model of how the team works.

And then there is a third kind of team.

Imagine a situation where two people are trying to find a missing person. They’re entering the woods and one person is following the path where the missing person was last seen heading. The other person is looking in a parallel path. The team has success if either one of them finds the missing person.

Unlike the first two team types, this one only requires one teammate to be successful - just find the missing person. The concept to set it up is the same as above: average players should feel that the expected credit or blame is the same regardless of the role. And the solution ends up:

where the “winner” is the teammate who found the missing person. The credit is dependent only on the chance that the “winner” had of finding that missing person, not the chance that the other teammate had. The blame, though, is dependent upon both player’s chances

For the missing person, we can assign some numbers. Let’s say that the teammate who was following the path of the missing person has a higher chance of finding them, say, 75%, versus the teammate on a more unlikely path with a chance of 40%. If the first teammate finds the missing person, they receive 62.5% of the credit, the other one getting 37.5%. If the second teammate finds the missing person, they receive 80% of the credit.

This is nowhere close to 100% for the person who accomplished the task. In this kind of team game, you want more people involved, which increases the team’s chance to succeed by simply having more people trying.

In this case, there was an 85% chance of finding the missing person, meaning that there was a 15% chance that the team failed. Upon failure, then the first teammate receives 67.5% of the blame, the other 32.5% to the second one.

If the input probabilities were different - that both players had a 40% chance of finding the missing person, for example - the credit to the teammate who made the find would be 80%, the same as before for the second teammate. But the blames upon failure would be equal at 50%.

What about that situation where a wife asked her husband to remind her to go to the drug store? How does that one work?

The first thing that matters is that she goes from having to remember things herself to asking her husband to remind her. She is expanding her team. Just by doing that, she gets credit for the increase in the chance of remembering. If she and her husband both have a 60% chance of remembering, the chance for the job to be done goes up from 60% to 84% just by her bringing him in on the job. She gets 100% of the credit for the 24% increase.

Scoreboard: 24% her, 0% him

Next, let’s say that the husband remembers. This task was accomplished and the chance goes up the remaining 16%. For remembering, the husband gets 70% of that 16%, or 11% (based on the cwinner formula). At the end, the total credit given over the two steps is 29% for her and 11% for him, totaling the 40% gained from when the wife reminded him.

If instead the wife remembered, she gets the 70% of that remaining 16%, meaning that she ends up with 35% and he has 5% of the 40% total gained.

In the case where they both forget to go to the drug store, the team lost the 84% all the way down to 0%. The loss of 84% is split evenly because they both had a 60% chance to remember. So the husband loses 42% and the wife loses 42% from her initial gain of 24%. The final scoreboard is -18% for her, -42% for him.

This is going to get me in trouble, but… those are the numbers that should make this a happy marriage. (I’m guessing marriage counselors would have put a halt to this whole analysis a long time ago.)

This whole analysis is about the team, whether that team is a husband and wife, a thrower and a catcher, a basketball team, a student and a teacher, or any of hundreds of things. A team is basically just a collection of people working together towards a shared goal.

The context of a team changes the reward system for the players on the team. An individual who does their job gets a positive reward, but an individual who does their job as part of a team that doesn’t achieve its goal gets some part of the blame. There are some team players that have the mentality, “Hey, I did my job, it wasn’t my fault.” But that’s not right. If they’re part of a team, they share some of the fault.

Or imagine a case where two teams of two players are competing against each other by sending their teams into a simple 100 m dash. The team whose player finishes first wins. On a team, the individual that won the race doesn’t get 100% of the credit. In this case, that winner only deserves 87.5% of his team’s credit, 87.5% of the medal, 87.5% of the points given to the team.

This is, I will emphasize, for “microevents”, not for the “macroevents” like the one where the wife wanted to get to the grocery store. There was no easy way to divide the credit or blame in the “macroevent”. That involved just two microevents - asking her husband to remind her, then actually remembering - and life often has much more than two microevents leading to an outcome. That’s definitely true for what happens in politics or a corporation.

This division of credit and blame approach makes sense at the micro level and, if you can document all those micro levels, as you can in sports, you can arrive at credit and blame at a macro level.

To be clear, this division of credit and blame is only among teammates. Blaming the weather for cancelling your kid’s birthday party - that’s fine, but it’s not what we’re talking about. The weather isn’t on your team.

Blaming a gust of wind for your errant throw in a game of catch doesn’t change the division of blame between you and the catcher.

If you’re playing basketball and you throw a pass that a defender accidentally knocks into the basket, that defender doesn’t get credit. That defender gets blame because what happened went against his goal. The offensive players split the credit and that random bit of luck mostly evens out the credit across them.

Giving credit to coaches is a different thing. What happens on the court is due to those players on the court. The coaches, at least in the way I’ve laid this out, get credit for making their players better, increasing their actual chances of having success, not for actually executing the game plan.

The division of credit and blame may not have any real application outside of sports where data is plentiful. The real world doesn’t have such detailed data on what people are doing. The real world’s jobs are really not monitored and, even if they were, it’s often hard to track what people are thinking, an important part of a lot of jobs.

Even if we had that data, it can be hard to assign some of the probabilities used in dividing credit and blame. It’s hard enough to do that in sports where we know what they’re trying to accomplish. We don’t know the insides of what a political campaign is trying to accomplish or what a corporation is doing by restructuring. We can think about it and maybe get more data.

But even if we had the data and improved our thinking about this, there is a bigger issue that keeps this from going beyond sports teams. It’s simply that we don’t know what is a team in the real world and who is acting for what team. We don’t know if you’re playing on your own individual team - a kind of capitalist dream where every individual maximizes only their own happiness - or playing for your family, for your school, your company, your industry, your state, your political party, your god, your country, mankind, or life on this planet. Hell, you don’t know how you’re balancing those things in your own mind.

We in the real world don’t know what team we’re playing for half the time. Or maybe we don’t know how to balance the trade-offs of one team vs another. It’s a lot easier to just “feel like” doing something and not think about how it fits together.

I thought about it a lot. I think it’s interesting. I don’t know how to answer what team we play for and when. But maybe if someone figures that out, they will care about how to reward people appropriately for those teams. I did.

![b_catcherBadThrowBadCatch = [1 + (p_catcher - p_thrower)] / 2 b_catcherBadThrowBadCatch = [1 + (p_catcher - p_thrower)] / 2](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!PV_T!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F7c63e729-2ad3-4519-bab7-bb61a560b85e_911x119.png)

![c_winner = [1 + (1 - p_winner)] / 2 c_winner = [1 + (1 - p_winner)] / 2](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!FzGD!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F5f26edb5-a550-471c-81ed-e42d67582848_584x106.png)

![b1 = [1 + (p1 - p2)] / 2 b1 = [1 + (p1 - p2)] / 2](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!BuqV!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F3929620d-7fbc-4303-9c32-7c017b74d0f9_418x111.png)

I continue to be absolutely and genuinely amazed at the way you think Dean😅😅😅

Fun read, Dean. To me it’s a commentary on objective thinking vs subjective - understanding the objective, aligning on clear roles and goals to achieve the objective, then attempting to execute. Naturally, in the execution period things happen that inform whether or not an objective was achieved - and a feedback loop can exist (w/ enough introspection and/or data) to modify the execution piece - or perhaps the roles & goals (toggling starters & 6th men) - to, hopefully, achieve the objective in the next test period (game). Alignment of who’s doing what, and when / how / where, is critical to ensure everyone is working interdependently while working toward the same goal. It’s the same in startups too. Data-driven decision making, interdependence, alignment on objectives.